Gerrymandering is one of those classic American problems — alongside high prescription drug prices or overpaying for medical care — on which most Americans agree but little progress seems to be made. In two-thirds of U.S. states, elected politicians get to redraw the boundaries of political districts, often for political benefit, despite the practice being highly unpopular among everyday Americans. In a poll by The Factual of 573 readers, 88% said that redistricting should be handled by independent commissions rather than elected officials, thereby limiting the ability of state legislatures to alter district boundaries for political gain. At the national level, polls in 2017 and 2019 showed that more than 70% of voters from all parties agreed the Supreme Court should limit the practice.

Gerrymandering has been decried by leaders of both parties for decades. In 1988, Ronald Reagan said “That’s all we’re asking for: an end to the antidemocratic and un-American practice of gerrymandering congressional districts . . . The fact is gerrymandering has become a national scandal.” Almost 30 years later, Barack Obama would say the same: “We’ve got to end the practice of drawing our congressional districts so that politicians can pick their voters, and not the other way around. Let a bipartisan group do it.”

So, how bad is gerrymandering today and why haven’t we comprehensively addressed the issue? This week, The Factual used 28 articles from 21 sources across the political spectrum to examine the state of gerrymandering in the latest round of redistricting, who is responsible, and why methods to address it have only met with limited success.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Who Is Responsible for Gerrymandering?

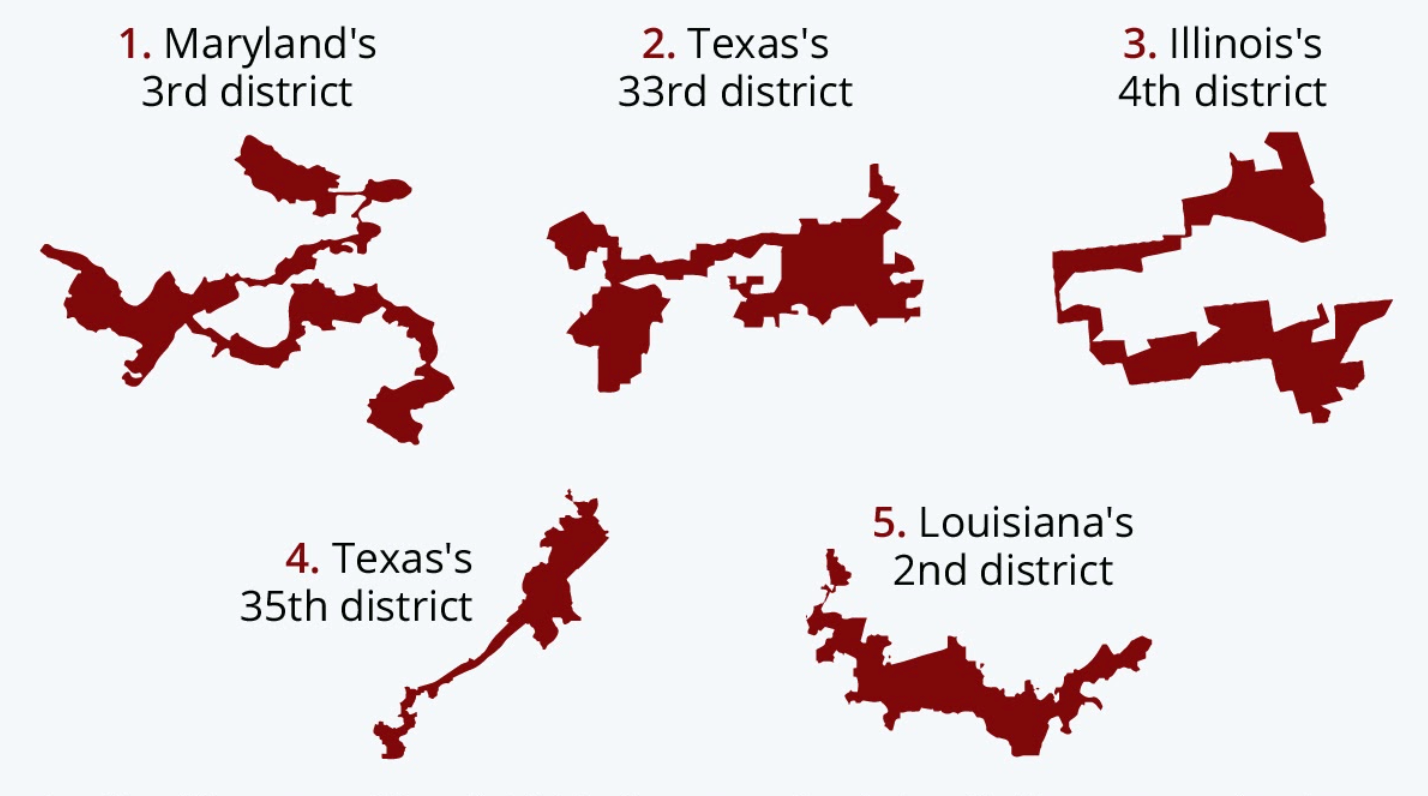

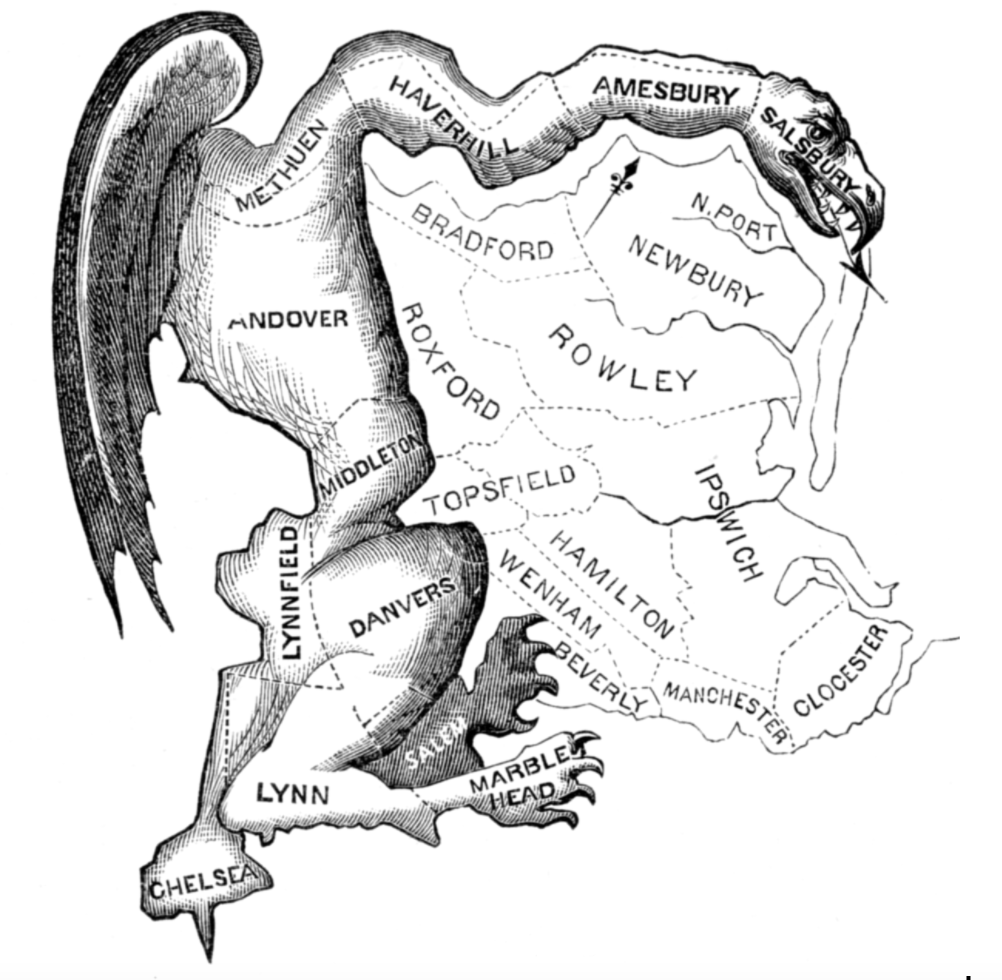

Gerrymandering is an age-old manipulation of representative politics, first brought to Colonial America by English settlers. The practice involves manipulating the shape of political districts to benefit a specific party. This usually takes two forms — cracking (splitting up a group of voters into separate districts) or packing (concentrating a group of voters into a single district) — all with the intent of limiting those voters’ influence in the relevant political body. And though the practice has been frowned upon since its early days in America, it continues into the modern era.

In 2021, the process is dominated by the Republican Party, which at present is likely to enjoy a net gain of five seats in the House through the redrawing of district lines alone. That means that if voters were to vote exactly as they had in 2020, new maps that “crack” and “pack” voters into new districts, sometimes in outlandish shapes, would ultimately result in five additional House seats for Republicans in the next election. This practice has led to headline imbalances in terms of representation. In Georgia and Texas, new maps would see Republicans win over 60% of the districts despite Trump winning in each state with roughly 50% of the vote. In other states, the gap between voter preferences and elected representation is starker. North Carolina, which Trump won with 49.9% of the vote, will likely see Republicans take 71% to 77% of the districts. In Ohio, Republicans could win at least 80% of congressional seats though Trump only won 53% of the vote.

Though Republicans are responsible for a majority of such gerrymandering in the current process, Democrats are by no means free of blame. Prominent examples from Illinois and Oregon demonstrate how gerrymandering, to a degree, remains a bipartisan practice. In Illinois, new maps would effectively reduce Republican districts in the state from five to three, leading the New York Times to call the maps “among the most gerrymandered in the country.” Likewise, Oregon could have had two potentially competitive districts for Republicans to target, but a new map drawn by state Democrats would see both districts become safely Democratic. According to the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, 3 of the 4 worst instances of gerrymandering are in Republican states currently, though New York (Democratic) may also end up making the list. In effect, Democrats are guilty of gerrymandering as well, just on a smaller scale.

How Bad Is Gerrymandering Today?

Traditionally, gerrymandering has been most commonly used and thought of as a way to gain additional seats while taking seats away from one’s opponent. This year, however, the practice is being used far more often to make previously competitive districts safer for the incumbent party. As Professor David Hopkins of Boston College told the Washington Examiner, “What we’re seeing much more commonly is the shoring up of vulnerable Republican districts and turning them into much safer Republican districts.”

This strategy is also influencing entire states. In Texas, new maps effectively counteract demographic changes to keep districts safely Republican. Despite 95% of the state’s population growth over the last decade being attributed to people of color, the number of congressional districts which are majority Hispanic or Black — and therefore largely left-leaning — will actually fall according to new maps. Meanwhile, the number of majority white districts will rise. In the suburbs of Houston, one of the district boundaries cleaves a prominent Asian and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community in two, pairing sections of Houston with broad swathes of rural, predominantly white voters. Members of the community say the decision leaves them without adequate representation.

On the surface, this round of gerrymandering may actually seem less problematic than past ones. In 2011, for example, Republicans gained 15 House seats from new district maps alone, three times as many as today. But experts warn that the current focus on making more “safe” districts is similarly problematic, particularly because it will lead to increasingly partisan politics and encourage extreme positions.

Competitive districts force parties to compete for voters in the middle, leading to more centrist and mutually agreeable outcomes. Lopsided districts, on the other hand, lead to more one-sided policymaking and the alienation of constituents. While roughly 51 of the 435 seats in the House are competitive, this year’s redistricting could reduce that number by a quarter, representing a big loss in a country built on political debate and compromise. As Edward Foley, a constitutional law scholar at Ohio State University, told the New York Times, “It used to be the people’s House, elected every two years to make it the most responsive. By eliminating competitive districts, you’re making it the least responsive.”

It’s worth pointing out that some argue that fixing gerrymandering will be no panacea for American democracy. These perspectives commonly highlight that gerrymandering can be overblown, that oddly shaped districts are not necessarily partisan, and that partisan differences would find other ways to manifest, even with fairer maps. That said, most see it as a major, pressing issue — and one that we have the tools to fix.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Stopping an “Un-American” Process

Progress on combating gerrymandering has been made over the last decade through the creation of independent or bipartisan commissions for redistricting. The general idea is that an independent commission, when informed with apolitical data and sufficiently insulated from political pressures, can create district maps that most accurately and fairly represent constituents. Bipartisan commissions, likewise, are built on the idea of generating maps that are sufficiently agreeable to both parties and therefore are likely to not be imbalanced. Today, just 11 states have redistricting commissions, while 33 still rely on legislative bodies. This means that the vast majority of states remain vulnerable to gerrymandering.

Efforts to adopt such commissions face obstacles on several levels. The most obvious obstacle to reform seems to be purely political — in such a partisan time, neither party really wants to cede any ground to the other, even in the name of free and fair democratic representation. In Ohio, for example, a 2018 ballot initiative showed that 75% of voters favored a bipartisan redistricting commission. Instead, Republican legislators this year drew new maps in secret and swiftly passed them, even excluding some of their Republican counterparts who support fairer maps from the process. Particularly in places that are experiencing significant demographic change (e.g., Texas and Illinois), legislators may see favorable maps as the best way to retain power, be it individually or for their respective parties.

Addressing gerrymandering is also being complicated by the federal design of American democracy. Because there has not been federal legislative action to address gerrymandering, states are left to their own devices in fixing the problem. This is creating a piecemeal response that further disincentivizes reform. For example, Democratic states represent the vast majority of those that have committed to having independent commissions for redistricting. This year, such commissions will draw 95 districts that would have otherwise been Democrat, compared to just 13 that would have been Republican. In this sense, Democrats may eschew adopting redistricting commissions in other states, wary of ceding the ability to manipulate redistricting when Republican-leaning states are unwilling to do the same and continue to benefit from its practice.

Otherwise, legal challenges are meant to mitigate problematic maps, but the process is imperfect and takes time. A decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2019 left the issue of gerrymandering up to Congress, effectively negating the value of challenges at the federal level. Now, the issue is being addressed at the state level, particularly as voting rights and equal representation is nearly ubiquitous in state constitutions. This creates other problems, however, including that many states have politically lopsided courts (Ballotpedia estimates that the courts in 27 states are tilted Republican while only 15 are tilted Democrat).

Due to changes to the Voting Rights Act in 2013, the bar is also lower for states to prove that their maps do not cause harm to specific demographic groups. Since the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, Texas, for example, had been under particular scrutiny for creating maps that disenfranchise Black voters. In every decade since, federal judges have found Texas maps to violate federal protections for voters through redistricting. The same goes for Ohio, where district boundaries split Black communities apart. Now, those affected have even fewer ways to mitigate problematic maps for legal reasons.

Conclusion

Even if Americans agree that gerrymandering needs to go, a real fix for the problem remains a long way off. The type of federal legislation that could fix the issue, currently contained within the proposed Freedom to Vote Act, is unlikely to pass the Senate due to the filibuster. Moreover, politicians on both sides are disincentivized from addressing it, since doing so could realistically reduce their power or that of their respective parties. In the interim, Americans will be left with imperfect, time-consuming tools for combating partisan gerrymanders, and lopsided maps will likely negatively impact the tenor and efficiency of American democracy.

Want to Hear More From The Factual?

Our daily newsletter delivers the best journalism on trending topics every morning.