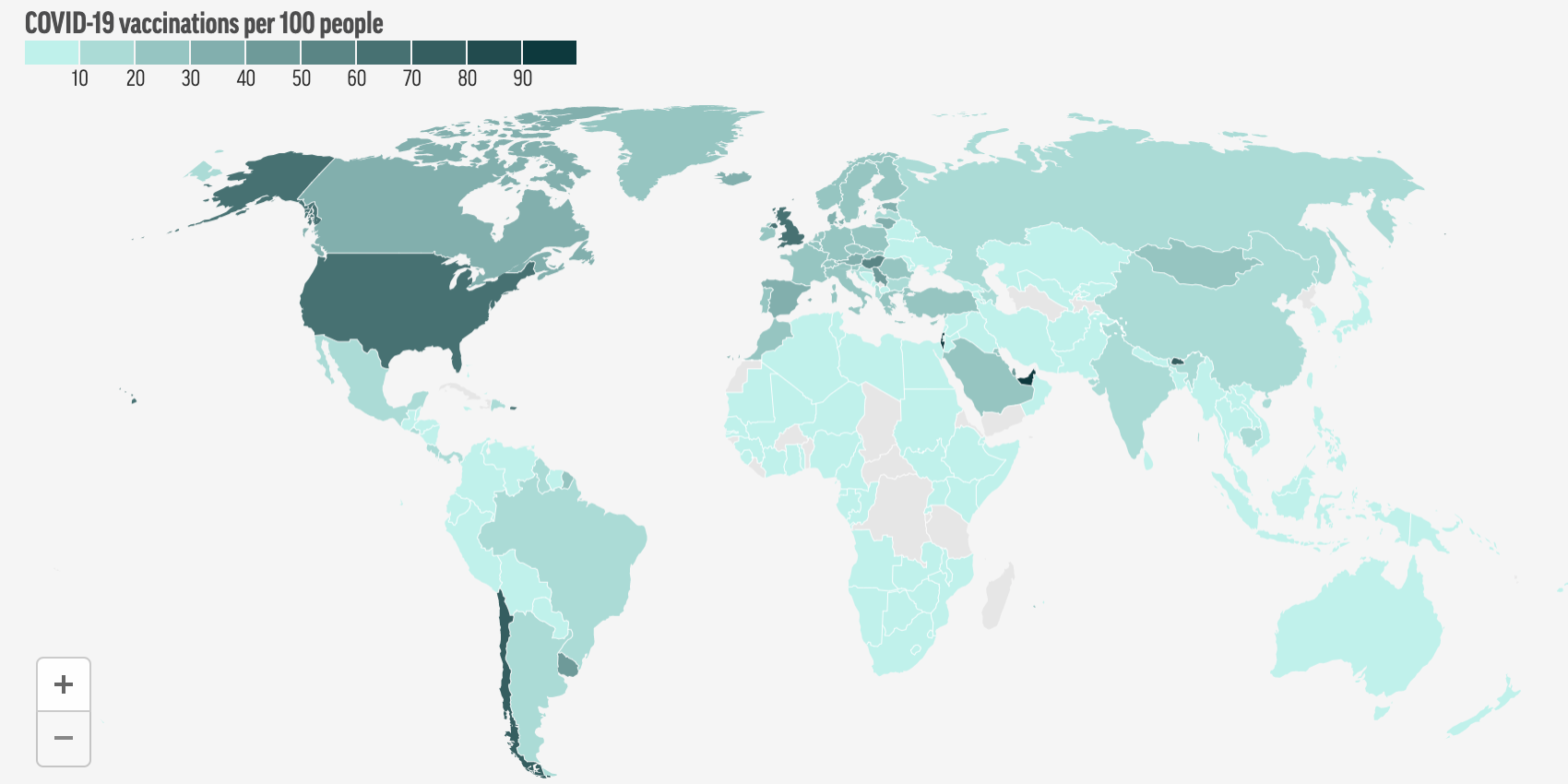

The Biden administration’s efforts to vaccinate millions of Americans have achieved great success in 2020, on the back of programs like Operation Warp Speed, initiated by the Trump administration, but a new dilemma is rapidly becoming clear: the world desperately needs more vaccines. The world has administered a billion vaccines so far, the vast majority of which — 87% — have been delivered to rich countries. Meanwhile, low and middle-income countries are bearing the brunt of new Covid waves, with potential long-term implications for the U.S.

India and a host of other countries are facing daunting outbreaks, partially brought about by new variants and by complacency that led places to open too far, too quickly. New cases are appearing faster than ever. In India, those totals have brought about a catastrophic failure of health infrastructure, quite literally leading to people dying in the street for lack of open hospital beds and to hospitals running out of oxygen. So, does the U.S. have the means to forestall successive crises around the world?

This week, The Factual looks at 36 articles from 25 sources to explore the interplay between vaccine deployment in the U.S., a rising global pandemic, and the possibilities and limitations of engaging in greater vaccine sharing abroad, including the potential sharing of intellectual property.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Does the U.S. Have Enough Vaccines to Share?

Even with recent hiccups, like the temporary pause on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, vaccine distribution in the U.S. has been a big success for the Biden administration. At time of writing, over 40% of all Americans had received one shot and nearly 30% were fully vaccinated. Experts hope the U.S. can reach herd immunity in the coming months, though some debate remains about what level of vaccination uptake will be required and how we can reach it. If the number is on the lower end, we may get there this summer. If it’s more like 85%, the timeline is more drawn out, and may not even be entirely feasible.

A significant, though shrinking, portion of Americans express skepticism about getting a shot and indicate they don’t plan to receive one. While that may change over time, particularly as messaging about vaccine efficacy and safety improves and circulates, there are already vaccine surpluses forming across the U.S. In some states, vaccines sit idly, and in others health providers are moving quickly ahead of schedule. Meanwhile, states are set to receive a total of 14.5 million doses per week, leading to huge surplus predictions — anticipated to reach 600 million doses in the second half of 2021. Looking abroad, this is raising difficult questions about what the U.S. can be doing to help combat Covid-19 abroad. Indeed, in part due to public pressure, the Biden administration took a major step on Monday by pledging to share 60 million doses of unused AstraZeneca vaccines “as soon as they become available.”

Source: NPR

That’s not to say the U.S. hasn’t been committing resources otherwise. The Biden administration recently pledged $4 billion (far more than any other country) to the COVAX Facility — an initiative meant to secure doses for some of the world’s most vulnerable populations. Separately, it has chosen to “lend” 4 million AstraZeneca doses to its immediate neighbors, Mexico and Canada. But countries around the world continue to decry the uneven distribution of vaccines, some even going so far as to call it “vaccine apartheid.” The administration’s commitment to share more AstraZeneca doses is a start, but long-term action is needed, and the political forces at play are complex. Most Americans want to help internationally — but only after U.S. citizens have all been given a chance to be vaccinated — and the Biden administration was reluctant to commit vaccines abroad, fearing the move would be unpopular to the domestic audience. At the same time, the urgencies of vaccine diplomacy will continue to demand concerted U.S. effort, especially to counteract the efforts of authoritarian states like Russia and China. Epidemiologists will argue that these considerations are besides the point — controlling the virus anywhere demands controlling it everywhere.

India, Others Crushed Under New Outbreaks

After weeks of improving numbers in the U.S., one could be lulled into the belief that the pandemic was approaching its end. But on the other side of the world, cases are rising faster than can be fully measured. Day after day, India is seeing more than 300,000 new cases, marking a record for any country in a single day. Beneath those headline figures are health services crumbling beneath a surge in cases. Acute shortages in essential medical resources like ventilators and oxygen mean that manageable symptoms of Covid-19 are going untreated — and people are dying as a result. Lesser but severe outbreaks are spreading elsewhere, from Brazil to Turkey to France.

The reasons for India’s outbreak are familiar. Politicians encouraged opening up, seeking to take credit for successfully handling earlier surges and eager to restart the economy. As with elsewhere, this may have been done too quickly. Populations began loosening up adherence to mask wearing, social distancing, and other measures, especially with vaccine deployment hitting nearly 4 million per day. Amid this false sense of security, and even with case counts starting to rise, politicians held huge campaign events and permitted large religious gatherings, jumpstarting a surge in cases. Making things worse, a particularly virulent strain of the virus, B.1.617, is thought to be behind the surge, appearing in individuals who already had antibodies to earlier strains. The stark reality of India’s vaccination effort thus far is that only 1.6% of the population has been fully vaccinated, far from what is needed to stop the disease from spreading. Indeed, at the current rate, it could take years to achieve herd immunity.

Source: Firstpost.

This is concerning for the U.S. for two reasons. First, as long as the virus is allowed to circulate or run rampant abroad, there is an acute threat of further mutation of the virus to a strain that is more transmissible or that could, conceivably, negate much or some of the protection afforded by current vaccine efforts. Second, production decisions made in the U.S. and Europe have been slowing down global vaccination efforts not just in India, but around the world. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have leveraged the Defense Production Act to give priority to domestic producers of Covid vaccines, essentially letting them “jump the queue” for supplies critical to the production of vaccines. That has been at the cost of global producers like the Serum Institute of India — responsible for making 60% of the globe’s vaccine supply, including much of those to be distributed through COVAX. In recent weeks, India has had to limit vaccine exports abroad and has seen vaccine production fall markedly due to bottlenecks in critical supplies from the U.S. — vaccine centers ran out of supply in as many as 10 states.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Can the U.S. Do More?

In the last few days, the Biden administration has made some big new steps to help combat outbreaks abroad and fix problematic policies. By committing to sharing AstraZeneca doses and pursuing a partial lifting of a ban on the export of critical raw materials for vaccine production, the Biden administration seems to be pursuing some of the more feasible and less legally tenuous options for doing so. These actions may act as an immediate pressure release valve, signalling to international partners and concerned Americans that the administration is taking the global vaccination effort as seriously as the one at home. However, more thorough, long-term commitments may be needed, even demanded, as the world tries to fully mitigate the effects of Covid-19, a reality that has triggered the debate about vaccine intellectual property (IP).

For months, affected nations around the world have been petitioning the U.S. and other wealthy nations to temporarily suspend IP restrictions on vaccines to permit other countries and companies to produce the proprietary designs of vaccines like Moderna, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson. The belief here is that expanded access to the ability to make these proven vaccines could help more people get access the world over. Proponents of the measure take a two-pronged argument: (1) that it is a moral imperative to save as many lives around the world as possible, and (2) that it makes economic sense to do so, since the quicker the world is vaccinated, the quicker the global economy can fully reopen.

However, there are no shortages of doubts about this approach. For starters, critics raise doubts about whether such a move is needed, given the alternative routes to access and the precedent this might set for the appropriation of private companies’ products. Some argue a temporary suspension of IP might deter further innovation from these companies, since they would have no guarantee on their ability to make a profit (however, it’s worth noting that public spending enabled many of the vaccines in the first place). There are also concerns that the world has already reached the maximum capacity of vaccine production, given available infrastructure. Even if vaccine IP was shared, it may not make a difference in the rate we can produce vaccines. Though the Biden administration is now reportedly considering a temporary suspension of IP restrictions, the efficacy of such a move remains to be seen, even if it has an obvious moral appeal.

The U.S. will continue to receive calls for help, and the decreasing urgency of the outbreak at home will enable it to commit more resources abroad. The key decisions this week represent an important shift in the Biden administrations policies, but questions remain about how far the U.S. response will or should go.

Note: This Google Sheet lists articles used to inform the findings of this article and indicates how the articles scored according to The Factual’s credibility algorithm. To learn more, read our How It Works page.

Interested in hearing more from The Factual? Our daily newsletter uses the credibility algorithm to analyze 10,000+ articles every day to highlight the very best journalism on trending topics.