We are experiencing some of the deadliest days in American history, but the magnitude of the ongoing disaster defies human comprehension. As the number of Covid-19 cases and deaths climbed during 2020 and reached new heights in 2021, search volumes for Covid-related terms, specifically “cases” and “deaths,” have not followed suit. One might think that concern about the pandemic, measured through these metrics, would closely follow the severity of the disease. Instead, we are seeing just the opposite: people’s interest has, if anything, declined as the disease has intensified. Why is this and how might it be affecting our response to the pandemic?

As the U.S. trudges through the deadliest period of the pandemic so far, The Factual set out to explore why Americans seemingly care less and less about a disease that is killing thousands prematurely every day. We reviewed 31 articles from 26 sources across the political spectrum to examine human responses to immense suffering and why American’s may be numb to the ongoing impacts of Covid-19.

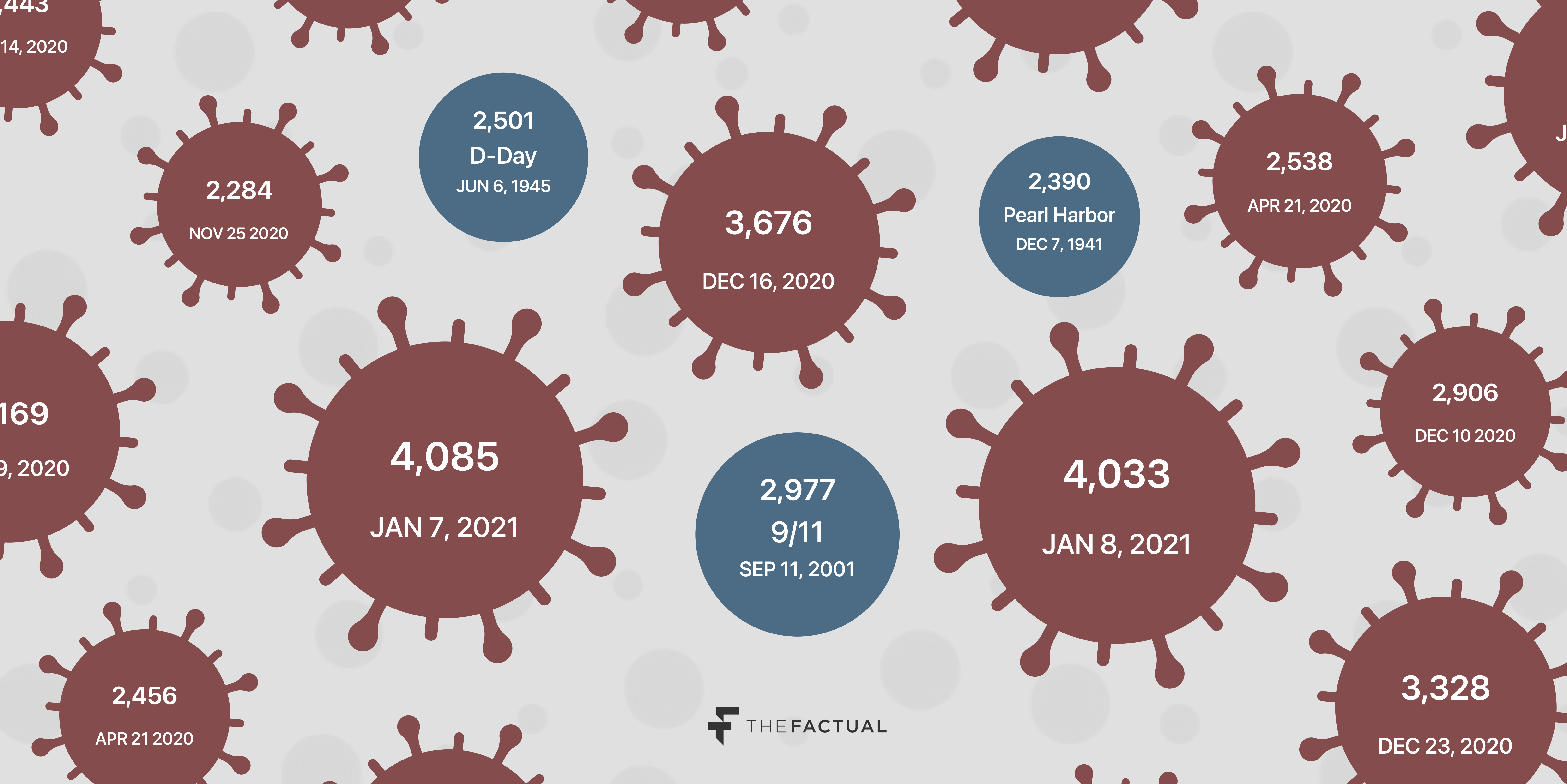

These circles represent some of the deadliest days (from a single cause) in the last 100 years.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Declining Searches for “Cases” and “Deaths”

More than 370,000 Americans have died from Covid-19, with the daily death toll at its highest yet in recent days. On January 7 alone, 4,112 Americans died. That’s the equivalent of nearly 30 standard 737s crashing in a single day, each loaded with 138 people. It’s more American deaths than from D-Day in 1944 and more than from the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. No matter how we split up and conceptualize these numbers — a tactic journalists use to make impacts more tangible — we fail to capture each of the individuals that these statistics include.

As thousands die, Americans are seemingly paying less attention. According to Google’s tracking mechanism for online searches, Google Trends, interest in “cases” and “deaths” peaked the week of March 22, when cases were rapidly surpassing the 100,000 mark but fewer than 50 Americans had died. (The search terms are closely linked, but not exclusive, to the Covid-19 pandemic.) Smaller peaks appear the week of June 21 and, to a lesser degree, in the weeks prior to Thanksgiving — times when warnings were abound about an impending spike in cases.

But in the subsequent peaks in Covid-19 deaths, and now, with more than 2,000 deaths every day for the last month, searches for these terms have failed to match the severity of the disease (note, however, that searches for “covid” generally have been consistent with trends in severity). For example, searches for “cases” and “deaths” are now at roughly a quarter of their March and April 2020 peaks, even as 10 times as many cases appear every day and twice as many people die.

This counterintuitive divergence seems to be explained by a combination of psychological, political, and demographic factors. However, at the very least, our inability to comprehend such widespread death continues to undermine our pandemic response.

Note: Searches are measured on a scale of 1 to 100 from January 12, 2020 to January 9, 2021. 100 represents the highest number of searches in a given week over the time period.

Source: Google Trends and Our World in Data

Psychological Factors

The most common explanations have to do with human psychology and the way we think about problems. For starters, humans have a hard time comprehending large numbers and tend to downplay risk even as the numbers, and risk, increase exponentially. This inability to appreciate larger numbers plays out through “psychic numbing,” a phenomena which suggests that humans are far more impacted and attuned to first instances of danger but grow less worried as the numbers increase and the threat is prolonged. For example, the difference between no one dying and one person dying is quite large, but the difference between the 100th and 101st death is far less impactful.

As evidence, scientists have shown that focusing on individuals and personal suffering, rather than large numbers, is much more effective at attracting interest and attention. Popularly cited examples come from experiments like those conducted by Paul Slovic, a professor at the University of Oregon, who identified that people are far more likely to donate to help a single starving child than to help successively larger groups of children. Human behavior is prone to connect to individuals and circumstances where we feel we can have an impact. Increasing the number of people dilutes our ability to connect and our perceived ability to make a difference. This effect can be seen elsewhere, such as with wars and genocides. Slovic’s work, for one, demonstrates that in the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan genocide “subjects were less willing to send the same amount of aid to a refugee camp of 250,000 than they were to a refugee camp of 11,000.” This mechanism helps to explain how each additional Covid case or death does not equate to an attendant increase in risk or concern, and may even give way to complacency.

Furthermore, humans are far more attuned to immediate and recognizable risk, such as an armed assailant or an acute natural disaster. It is far more difficult to comprehend the true magnitude of a complex web of seemingly low-risk events, be it from a virus with a low mortality rate or from the incremental unseen changes of climate change. Both have effects that are spread over time and hard to capture in any single, concise event. This obscures the connection between human behavior and any positive or negative ramifications. Furthermore, as the symptoms repeat with increasing frequency — be it the 312,672nd death or yet another warmest year on record — each additional iteration tends to make less of an impact. As Melissa Funicane, a social scientist at the Rand Corporation, put it: “the average human who’s not a statistical analyst or epidemiologist, doesn’t have the tools you need at their fingertips to make judgements about something as vast and complex as the global pandemic.”

Political Factors

Another clear potential reason comes from the spurious narrative that many of these deaths are not actually due to Covid-19. A popular conspiracy even goes so far as to suggest that medical authorities are attributing deaths from a range of causes to Covid-19 in an effort to make the crisis more dire, spread fear, and permit stronger government action.

Source: Pew Research

These narratives have been repeatedly and soundly rejected, and many suspect the true toll to be even higher than the official figures. But whether or not people fully ascribe to the idea that deaths have been over-reported, it has played into doubt around the seriousness of the disease and whether official tallies and government warnings about its seriousness should be trusted. Arguments against the severity of Covid-19, such as that it is little different from the common flu, drive down concern about the virus, especially in more conservative populations. In December, Pew Research found that just 43% of Republicans see Covid-19 as a major threat to public health, compared to 84% of Democrats. Though there is fixation on Covid-19’s low mortality rate, now just below 2% in the U.S., there is a larger failure to recognize the scope of human suffering that mortality rate delivers across millions of cases, let alone from the 10% (or more) of patients who exhibit long-term effects. The severity of the disease, it seems, often fails to resonate until people are personally, and often irreversibly, affected, a dynamic that is not restricted to the U.S. or the issue Covid-19.

In hyper-partisan conditions, it is no surprise that as the disease became politicized, certain populations may have begun to pay less attention. If one doesn’t believe that it is as deadly or widespread as is being reported, there’s little reason to monitor its progress.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Demographic Factors

A final set of potential factors relates to specific populations that society consistently undervalues. These populations have suffered the worst impacts but are also those most commonly pushed out of sight, be it the elderly locked away in nursing homes or minority groups relegated to impoverished and underserved communities.

For example, Covid-19’s impacts are particularly acute on the elderly, who account for roughly 8 in 10 of those who die. In a range of experiments, scientists have shown globally that people consistently undervalue the elderly vis-à-vis others, generally falling back on the explanation that those with fewer years left to live are less valuable than those with many more productive years ahead. Even if each of these individuals may be a deeply loved parent, sibling, friend, or mentor, this implicit devaluation plays into an interpretation that the disease is one that specifically impacts the elderly and is therefore less of a concern.

The virus has had a similarly outsized impact on minority communities. Data suggests, for example, that Black, Latino, and Indigenous Americans are several times more likely than white Americans to both be hospitalized and die from Covid-19. In LA, the site of the country’s worst outbreak, Latinos account for 59% of cases and 48.5% of deaths, even though they only account for 40% of the population. Individuals from these communities make up many of the essential workers who continue to work in dangerous conditions and typically have less of a safety net to fall back on. In a country that has consistently underserved minority communities, especially in matters of public health, it’s no wonder that these communities suffer disproportionately and that the country as a whole — which is roughly 70% white — may be less attuned to the severity of the problem.

Source: LA County

American Deaths Will Continue to Go Unseen

These factors all play into our inability to fully comprehend and react to the Covid-19 crisis. As William Wan and Brittany Shammas wrote in the Washington Post, “without visual, physical manifestations of deaths, the alarm bells in our heads fail to ring … we don’t see the deaths, we fail to see their connection to us — including our role in preventing their growing numbers.”

The pandemic’s death toll in the United States will still likely exceed 500,000, and Covid-19 will undoubtedly remain a stain on U.S. history. Our response strategies now, especially our personal actions, are as important as ever. Ongoing vaccination efforts mean that immunity is just a matter of time — but also that each new death will seem that much more preventable. At the same time, new variants seem to threaten more dangerous outbreaks — and even further mutation of the virus. Perhaps, had we known of this reality with certainty from the very beginning, including that the virus would kill half a million Americans, more people would have taken the disease seriously and helped to mitigate its worst effects. Instead, the disease’s low mortality rate and beguiling symptoms, and our muddled responses to it, promise to leave many American deaths unseen.

Appendix

This appendix shows each of the articles used to inform the findings of this article, as well as how the articles scored according to The Factual’s credibility algorithm. To learn more, read our How It Works page.