In the first six months of 2021, 16 states in the U.S. have considered bills restricting critical race theory (CRT) from being taught in public institutions, and several have signed them into law. Against the backdrop of George Floyd’s death in 2020, which propelled discussions about race to an apex around the world, this juxtaposition may appear confusing.

What is critical race theory? Why is there a strong backlash against it? Does CRT advance or hinder conversations about racism in society?

This week, The Factual reviewed 45 articles from 31 sources across the political spectrum, to examine why people are so divided on CRT—and where there may be room to move forward.

What is critical race theory?

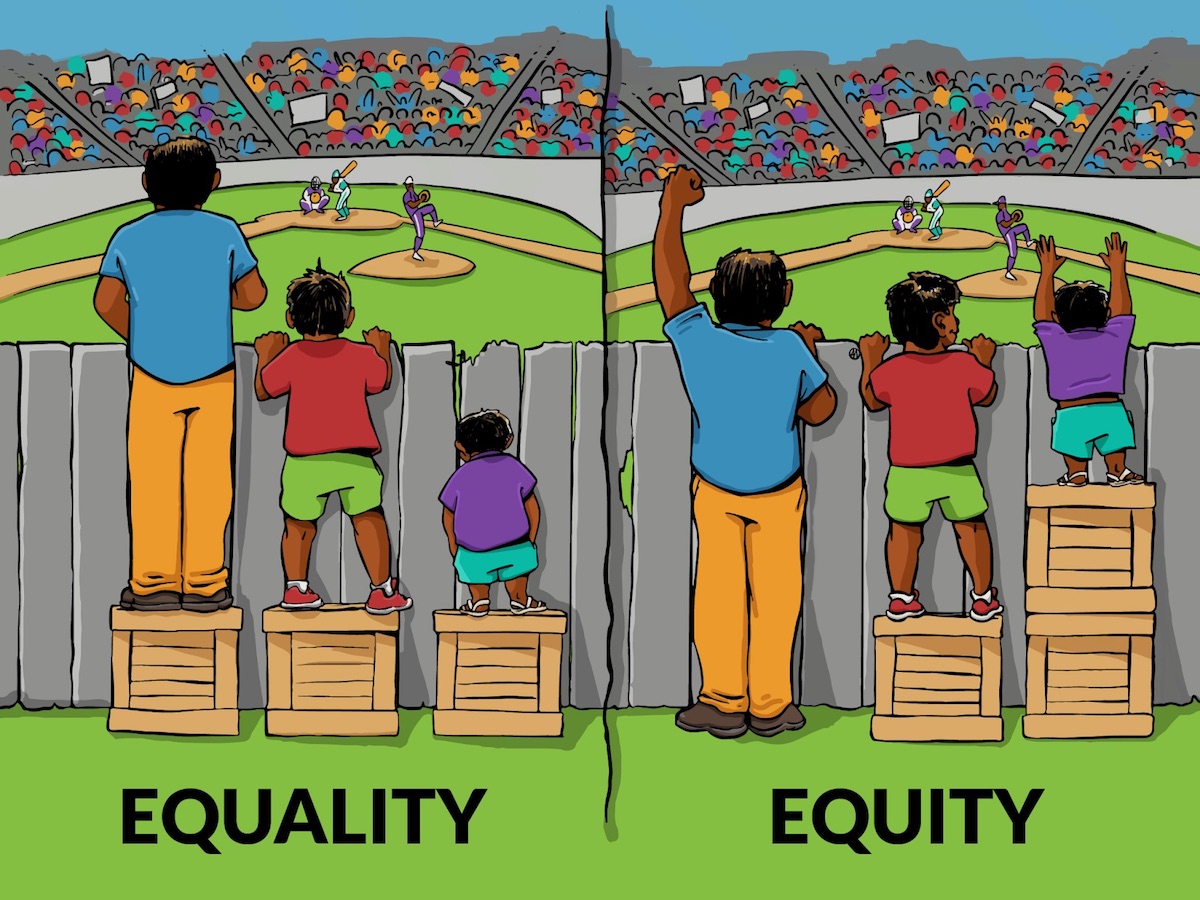

Critical race theory is a grouping of academic concepts that originated from the work of American legal scholars in the 1970s. These early analyses examined why the legal victories of the civil rights era had not translated to large-scale reductions in racial inequalities, with a recurring answer being that color-blind laws (laws that do not explicitly target racial groups) are insufficient in leveling the playing field.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

In the late 1980s, CRT became a broader movement in academia, growing beyond legal scholarship and entering other disciplines. A brief overview of key concepts:

- Race is a social construct, not a biological reality.

- Racism is systemic and/or institutional beyond simply manifesting in individual feelings of prejudice, and racism woven into legal structures negatively affects most people of color in different areas of life.

- Racism is a normal part of American life, not an aberration.

- White Americans inherently hold a degree of privilege as beneficiaries of systemic racism, regardless of whether they consciously hold racist views. Advocates generally do not believe white privilege equates to lack of hardship or poverty, simply that it is a type of privilege affecting many areas of life that other races do not have.

- People may be prone to an unconscious bias against those of other races.

- Intersectionality: various identities intersect and contain their own nuances (e.g., race and gender, gender and sexuality, etc).

- The “lived experiences” of people of color ought to be centered and is intellectually useful, even in an academic context.

What evidence do advocates and critics of CRT cite?

Evidence cited by advocates of CRT

The evidence advocates cite in favor of CRT is broad-ranging and often well-documented. Advocates often cite disparities in outcomes between racial groups in various areas of life. Most of these disparities are continuations of long-term trends that extend well into the 20th century (or even earlier). Prominent examples include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Racial disparities in policing and criminal justice. A review of relevant research suggests that black people receive more violent or harsher penalties than white counterparts, even when controlling for levels of criminality, demographic factors, etc.

- Racial disparities in education: college attainment has risen for all races, but a gap has persisted between white and black Americans since the 1960s.

- Disparities in health: African Americans suffer worse outcomes in many areas of health, have an overall lower life expectancy, and report worse experiences with health professionals.

- The racial wealth gap: Numerous metrics show African American households have considerably lower household wealth than other races, especially white households, a trend that has continued since the early 20th century. This racial gap persists even with households of the same income range (households in the top 10% income percentile still have a large overall net worth disparity).

- (A noteworthy exception: households in the bottom 20% income percentile have a median net worth of 0, whether the households are white or black. )

- Similarly, unemployment rates have historically been significantly higher for black Americans than whites. Black Americans are also underrepresented in top corporate positions, and on average earn less than white and Asian Americans, even when controlling for educational attainment.

- Rates of African American homeownership are considerably lower than rates for white Americans. One commonly cited reason for this is redlining: when the Federal Housing Administration actively discriminated against black people from the 1930s to 1960s. The FHA was intended to lower the barrier for homeownership by insuring mortgages, but neighborhoods with more black people were highlighted in red on maps and deemed ineligible for FHA-backed loans.

CRT’s recommendation for rectifying such inequities is to propose race-specific solutions, like reparations or affirmative action. Ibram X. Kendi, who wrote the 2019 book How to Be an Antiracist said that discrimination is racist when it creates inequity, but, “If discrimination is creating equity, then it is anti-racist.”

Those making the case for such race-specific policies justify it on the grounds that racism has had an all-encompassing impact in various areas of life. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” which has been cited by pundits on the left and right as a pivotal moment in the reparations debate, exemplifies this. Coates uses the Chicago neighborhood of North Lawndale as a case study of housing discrimination’s far-reaching impact. North Lawndale today, writes Coates, is 92% black and is “on the wrong end of virtually every socioeconomic indicator,” (with high rates of poverty, violence, incarceration, and infant mortality).

However, domestic and international examples of reparations suggest that race-specific policies are challenging to implement even for specific events that are widely seen as unjust.

Arguments cited by critics of CRT

While CRT has received pushback from across the political spectrum, serious critics rarely dispute America’s historical crimes or ignore existing statistical racial inequality. Critics of CRT tend to make at least one of the following arguments:

- CRT is divisive to a harmful extent (particularly when taught in schools and workplace trainings);

- CRT is effectively racist, and/or threatens progress against racism;

- CRT (or substantial portions of it) does not hold to academic rigor.

There is little data at present to suggest that CRT is divisive when taught in the classroom or workplace, but this is difficult to measure in the first place. This discussion has been navigated largely on a case-by-case basis, with critics pointing to an apparent trend of seemingly divisive and/or inflammatory content.

Prominent recent examples include leaked documents from Disney’s diversity initiative, which advises non-black employees against asking their black coworkers to educate them on racial issues, and leaked video of a Coca-Cola diversity training module that encouraged employees to “be less white.”

To the critics, such stories are directly attributable to CRT. But not all advocates of CRT would agree that these are serious applications of the theory, and many are quick to clarify that CRT is not about making white Americans feel bad. Instead, the argument goes, the goal is to center the traditionally overlooked experiences of people of color. Some advocates also contend that CRT is primarily concerned with the study of racism in systems, rather than individuals.

The second major critique, that CRT is effectively racist, stems from the charge that white Americans cannot be held responsible for the misdeeds of their ancestors, as well as distaste for a framework in which everyone is born into a category with inherent characteristics (“privilege” or lack of it). It also stems from a disagreement with CRT’s prescribed solutions.

When proponents of CRT critique color-blind policies, critics of CRT contend that race-neutral policies have been an achievement of American democracy and that steps to the contrary would be a regression. This is a point frequently raised in the context of universities’ use of affirmative action, which many conservatives view as discriminatory to Asian Americans. Commentary author Christine Rosen described race-based affirmative action as sorting “among non-white groups into deserving and undeserving minorities.”

Several African American critics of CRT have also described it as offensive to black people and/or empowering a racial hierarchy.

- The 1776 Unites project was created by black academics as a response to the New York Times’ 1619 Project. 1776 Unites claims to offer an alternative perspective that “celebrates black excellence” and “rejects victimhood culture.”

- In a New York Times op-ed, Thomas Chatterton Williams said reparations advocate Ta-Nehisi Coates’ views of whiteness were eerily similar to that of white supremacists, in that both view whiteness as uniquely and inherently powerful.

- In a 2020 article in The Atlantic, linguist John McWhorter described the best-selling book White Fragility (which critiques how white Americans view racism) as uniquely infantilizing to black people. In another 2018 essay for the outlet, he questioned the apparent importance of white Americans’ biases, writing “Are black hands truly tied because whites are more likely to associate black faces with negative concepts in implicit-association tests, especially when evidence suggests that the results do not correlate meaningfully with behavior?”

- Coleman Hughes has written numerous pieces disputing popular CRT notions, and has testified before Congress against reparations. From his testimony:

- “[…] The people who were owed for slavery are no longer here, and we’re not entitled to collect on their debts. Reparations, by definition, are only given to victims. So the moment you give me reparations, you’ve made me into a victim without my consent.”

In an opinion piece for Newsweek, Chloe Valdary made the case that the Jim Crow South inadvertently fostered black success—a nuance Valdary claims is lost in CRT, which she views as overly reductive.

The charge that CRT is racist is a particular sticking point in recent legislative efforts. A law barring CRT from schools in Idaho—which became the first state to pass such legislation in April—specifically prohibits educational institutions from teaching that any race, ethnicity, religion, national origin, or sex is inherently inferior or superior. The legislation claims this inferiority/superiority claim is “often” found in CRT.

Prominent CRT critic Christopher Rufo described the justification for such legislation as being in line with legal precedent banning discrimination from public institutions, writing that under the 14th Amendment, states and schools are obligated to prevent environments that perpetuate “racial stereotyping, discrimination, and harassment.”

As for concerns about academic rigor, critics rarely deny the existence of a disparity in outcomes between racial groups. They do, however, argue that such disparities may have other causes, and are over-simplified by CRT. Many writers also point out that large-scale disparities can be used to advance ideas that few advocates of CRT would ever take up. As John Staddon articulated in 2019 for Quillette:

Men notoriously commit more crimes, especially violent crimes, than women. We do not cry “sexism” when more males than females wind up in prison.

As our analysis of racism in policing pointed out, however, and as many CRT advocates will point out, black people statistically receive worse outcomes than their white counterparts even when accounting for criminality.

On the other hand, Staddon’s larger point is that disparate outcomes do not inherently prove anything about their causes. This overlaps with another commonly raised criticism: that systemic racism is an overly broad concept that quickly becomes difficult to prove, a relevant issue as academically rigorous theories ought to be falsifiable. From the Quillette article referenced above:

[Systemic racism] is almost impossible to prove, because racism is discrimination without any reason other than race. To prove discrimination, all other possible reasons—reasons like differential ability, interests, criminality, etc., as in the examples I gave earlier—must be eliminated.

Lastly, although the big critiques of CRT are conceptual disagreements, some specific findings have been questioned. One example is the purported effect of implicit bias: proponents of CRT posit that implicit bias could be a factor in lower employment rates among African Americans. Samuel Kronen disputed this notion in a 2020 Quillette article:

An infamous study in which black “looking” names received fewer call-backs from job recruiters provides prima facie evidence of discrimination on the part of the recruiters but no evidence that this is systemic. Furthermore, replications of the study have found similar results for Asian names. Given the astounding success of East Asian and Indian Americans, the original study’s findings can explain very little about the causes of the nationwide achievement gaps between blacks and whites.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

How is The New York Times’ “1619 Project” related to CRT?

The New York Times’ 1619 Project is a long-form journalistic effort to reframe American history with a significantly greater focus on the role racism played. As such, it also argues that 1619—the date African slaves first arrived in North America—marks the true year America was founded. The 1619 Project is all the more relevant to CRT’s critics because it has been taught in public schools, and the Pulitzer Center has made curricular materials based on the Project available on its website.

Although the Project was celebrated in some corners and lead author Nikole Hannah-Jones even won a Pulitzer prize for it, some of its claims have been disputed—particularly its opening argument that the American Revolution was largely an effort to preserve slavery. In late 2019, when several leading historians wrote a letter to the New York Times demanding corrections, the letter’s primary author said the 1619 Project’s use in school curricula was a motivating factor. (Note that the letter’s signatories offered praise for the 1619 Project overall, and simply had qualms with specific claims.) Eventually, the Times edited the introductory pages of the Project by softening some of the contested language, a development celebrated by conservative websites.

Broadly speaking, there is evidence in favor of both critics and the Project on the disputed material. Several historians who have weighed in are careful to note that history is complicated and slavery did play a large role in American history. Some of the conversation, however, is fundamentally an issue of epistemology—a question of how much importance should be lent to interpretation in the study of history, what constitutes a historical fact, etc.

What does the debate of CRT obscure?

The loudest criticism of CRT is that it’s an ideologically driven movement sowing unnecessary divisions along racial lines. The loudest reply is that efforts to curb CRT are tantamount to ignoring America’s historical crimes, and any injustices that persist today. This heated exchange sometimes overshadows other relevant questions, so to that end, here are a few points that may help advance the discussion.

When does talking about race become teaching CRT?

CRT’s concepts are so widespread, and so frequently disassociated from the theory’s name, that it is not always clear what might constitute teaching CRT. If a teacher simply discusses the concept of systemic racism in class as one available perspective, are they teaching CRT? Do laws like Iowa’s restrict how most teachers would discuss racism, or would it affect only a small minority of teachers explicitly teaching CRT with clear reference to the theory itself?

Even experts on critical race theory disagree about the extent to which classrooms teach it. Khiara Bridges, the author of a textbook about CRT, has said she does not consider schools’ increased focus on diversity to be part of critical race theory, while Kendall Thomas, co-editor of a foundational collection of CRT writings, believes that CRT has evolved such that some of what is now taught in schools’ history curricula qualifies as CRT.

Some schools use “culturally responsive teaching.” Culturally responsive teaching is an academic pedagogy that encourages teachers to be responsive to various cultural backgrounds, often by having students center their backgrounds in the classroom. The differences between these two CRTs may not always be immediately clear in practice. One public school district in Maryland came under criticism from parents for its apparent use of critical race theory, but the school district insisted it was using culturally responsive teaching instead.

Are there any “third ways” available for classrooms?

Writing for RealClearEducation, three law professors argued for a “third way” forward. Agreeing with both the conservative description of CRT as illiberal and the liberal description of attempts to ban it as affronts to free speech, the professors propose “a pluralistic civics education that teaches Critical Race Theory alongside numerous other approaches to social science and social justice.”

Can large-scale racial inequality be explained without racism?

A subset of the left—typically open socialists—believes the force attributed to systemic racism obscures the role economics plays in apparent racial disparities. In this mode of thought, historic injustices do matter, but are not the main forces causing inequality in recent decades. As a 2020 essay entitled The Trouble with Disparity stated:

It is well known by now that whites have more net wealth than blacks at every income level, and the overall racial difference in wealth is massive. Why can’t antiracism solve this problem? Because, as Robert Manduca has shown, the fact that blacks were over-represented among the poor at the beginning of a period in which “low income workers of all races” have been hurt by the changes in American economic life has meant that they have “borne the brunt” of those changes. The lack of progress in overcoming the white/black wealth gap has been a function of the increase in the rich/poor wealth gap.

In fact, it may surprise some readers to know that one of the 1619 Project’s harshest critics is The World Socialist Website.

Conclusion

Given each point raised until now—which is only a sampling of a much more complex discussion—one cannot be blamed for feeling a little confused or conflicted.

Critical race theory was pioneered by black scholars, while several of its fiercest critics today are themselves black scholars. Some historians think the 1619 Project is admirable but too flawed for schools, even as others in their field reject such concerns. There are progressives to whom CRT is foundational, leftists who dispute the very notion of systemic racism, and political moderates that have switched views of CRT in either direction.

With such an abundance of perspectives, on such a broad range of ideas, most simple answers are suspect. There is good news in that: at least the debate about critical race theory is also far richer than it first appears.

Appendix

This appendix shows all 45 articles from 31 sources across the political spectrum used to inform the findings of this article, as well as how the articles scored according to The Factual’s credibility algorithm. To learn more, read our How It Works page.