For centuries, societies were divided by the ability to read. Now, in 2020, with global literacy rates around 86%, the divide is determined less by the ability to read, and more by the ability to make sense of that information.

This is coined ‘media literacy’, and describes the ability to interpret information from a variety of mediums (text, video, audio, etc.) and process it both accurately and effectively. While this once began as an academic concept, it has now become a necessary life skill.

Media literacy is especially crucial at a time when we have all the answers to the world’s questions at the tip of our fingers, or a simple ‘Alexa…’ Processing information can allow an individual to form a worldview, make opinions, draw conclusions, and take action. While there are infinite benefits to living in a digital age, we are now faced with an unforeseen challenge: how do we make ourselves proficient processors?

Why is media literacy so important?

Our society will henceforth no longer exist without the influence of technology. We are surrounded by it in all aspects of our life, from obtaining our news to seeking the cause of our ailments. In both cases, we often turn to search engines for answers, clicking the top related link, and using that to form the basis of our understanding. The problem lies in the fact that, without a sense of skepticism, we often end our search there. Without careful thought, we take whatever comes up first as gospel. But what if the answer you received is incorrect? Or biased? Or misinformed?

Teaching in a middle school context, I often hear about the latest news trend once second students walk into the door. While I am proud that the digital era has made it easy for all people to stay in-the-know, I often worry that my students’ conversations around the news lack depth or context.

For example, the hottest news topic this year is coronavirus, or COVID-19. The instant a student sneezes in class, you can hear from the other corner: “Coronavirus!” This mentality is enforced by emotionally-charged articles from all perspectives. After searching “Should I be worried about coronavirus?” on Google, my top search result was: “How much should we worry about the new coronavirus?” published by The Hill. If my research stopped there, I would be relying on an article that scored 58% on The Factual’s credibility rating, leaving me under-informed in a conversation that should rely on facts and not sensationalism.

The ability to question the information we receive to ensure that it is of the utmost quality is a skill learned, not inherent. Those of us born in the digital age may have received media literacy skills through classes and schoolwork. However, even at my ripe age of 24 — the internet looks drastically different than it did when I was in secondary school. With a rise in ‘fake news’ and ‘disinformation’, to be able to navigate the internet users must be adaptive and dynamic. They must be able to process as quickly as the internet changes.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Teaching media literacy in schools

In the past four years, many schools shifted their curriculum to ensure that they included digital literacy. In middle school, we provide guidelines that students can follow to ensure that a source is reliable, based on five criteria: currency, relevancy, accuracy, authority, and purpose. However, I am still receiving submissions citing open-source publications like Wikipedia.

A recent study by the Stanford History Education Group demonstrated that while digital natives are likely to be adept at using technology, their efforts to determine quality, reliable efforts were “bleak.” The expectation was that middle school students could distinguish between an ad and an informational site, and high school students could determine whether the source was reliable to answer their questions. Of 454 high school students, only 20% showed mastery,

This means that while we have made strides, we still have long to go before we ensure our curriculum promotes digital literacy.

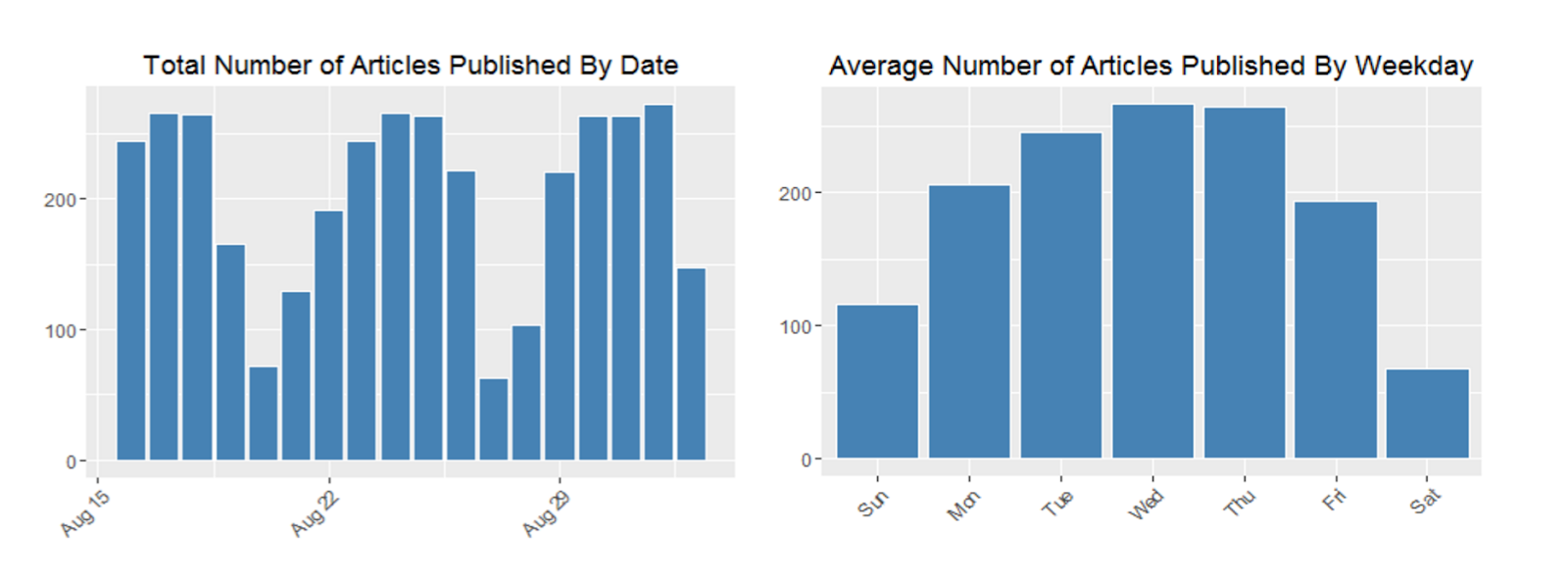

An over-saturation of media

Often, when developing media literacy skills, people ask where to begin. In a 2016 study by The Atlantic, Robinson Meyer found the Washington Post published 500 articles per day, including staff-produced, wire, and out-sourced stories. I find it hard to be able to read one article per day, let alone 500. And this is just one news source! This number exponentially increases when you factor in the number of news sources. On average, The Factual rates between 10,000-15,000 articles from the main U.S. news sources per day. Being able to sift through that amount of information seems overwhelming and unachievable.

The chart above models how many articles the Wall Street Journal publishes per day. With a range from 100-200 articles from just one source, we are confronted with a vast amount of information.

In a saturated space, readers need to be able to reason out what matters and what makes sense. Often, their first choice is to use articles that align with their beliefs to inform them, a phenomenon called confirmation bias. While this helps with the process of sorting information, it can underserve the reader by not challenging their beliefs.

To begin to sort through the amount of information out there, readers need to set high standards for their content. First, they should consider the expertise of the author and publication, the diversity of the sources they reference, and the overall quality and tone of the writing. Fake news is less likely to exist in an article that references multiple credible sources, and is in turn cited by reputable publications. To do this takes active effort to move away from clickbait headlines and instead invest time in reading full stories before coming to conclusions.

An ethical creator of media

In the digital age, it’s not only easy to believe unreliable information — it’s also easy to create it. To be media literate, we also must be aware of our own biases when releasing content. Whether we are commenting on a passionate Facebook post, or publishing a Tweet, or even sharing a photo on Instagram — we are adding to the wealth of information that exists. In doing so, we are inherently sharing our biases toward things we like, agree with, or disagree with. We’ve developed our own sphere of influence, whether it be family and friends, or the general public. To be media literate means to use our platforms, regardless of scale, ethically.

Steps to increasing media literacy

1. Consider the source.

This is important for both students in schools and older generations navigating social media. Where is the information coming from? Does the author of that information have a certain stake in the matter? Do they hold expertise over the subject? Can you find an author at all? These are the types of questions we need to be asking.

2. Determine the timeliness of the information.

Depending on the topic, something reliable three years ago may not be relevant today, as data is constantly shifting and we are able to draw new conclusions. I teach my students that five years is the cut off for relevant information in most cases. An outlier, for example, could be an article describing the physical features of an animal. In that case, the information was unlikely to shift over time.

3. Check for tone.

We’re all guilty of having bias, but is the author trying to contain their bias as much as possible? Are they forthcoming about their bias, but encourage you to make your own opinions? You can detect this from the language that they use. For example, emotive terms such as “devastating”, “embarrassing”, or “the best” all show an author’s stance on an issue.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

4. Use your judgment.

We should seek out sources that don’t tell us what to think. If the author presents facts, or a well-researched argument, we should be left with the space to reason out our own opinion. Take everything that you see with a grain of salt, and do not always rely on the most popular Google search as gospel on a topic.

5. It’s okay to seek help!

The process of building media literacy is complex and multi-faceted. We must begin by asking questions about the information we’re presented with. By maintaining a healthy level of skepticism, we are challenging the media to be better informed and less persuasive. Skepticism should direct us away from relying on a particular source for all of our information, and should guide us toward considering multiple perspectives before determining our own. This process takes time, and with the amount of articles published per day, is an impossible feat.

At The Factual, we help expedite the process by ranking articles based on the criteria listed above, and automatically tell you a source’s political-leaning and credibility rating. We also curate the top stories from each day and share them with our readers via an email newsletter. Throughout this process, we emphasize that we are here to present the best information, leaving it up to the audience to make up their own minds.