When I was a young boy, I saw that my father read two or even three newspapers daily. When I asked him why he didn’t just read one paper, he said “You should never trust any one source to tell you the whole story.” His advice remains even more pertinent today given the proliferation of news sources and increasing polarization in the media.

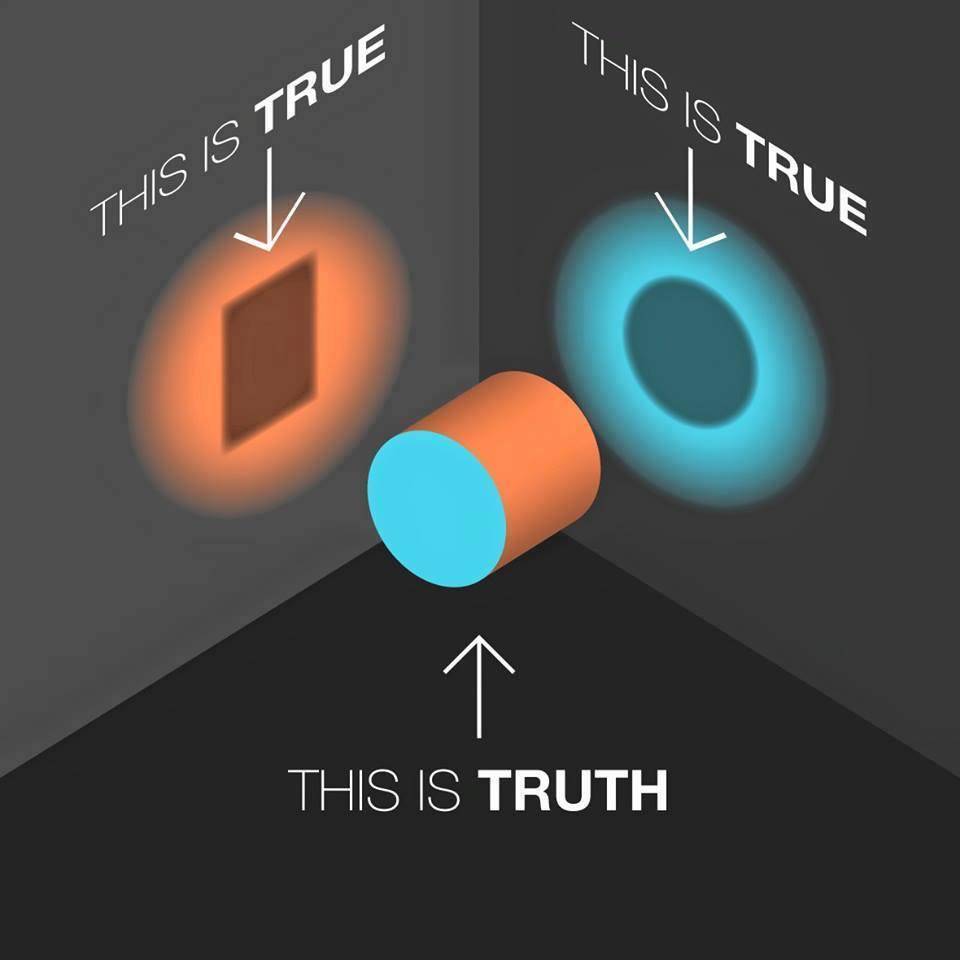

But people sometimes argue against this model, asking “what if one news outlet is telling the truth and the other isn’t?” Many noted journalists decry the idea of always needing to hear “both sides.” “Bothsidesism” is essentially the presentation of ideas as being of equal value without necessarily accounting for the strength of the associated arguments. So, are there always two sides to a news story?

Why Can’t the News Provide Just the Facts?

A common parable that journalists quote to push back against bothsidesism is “if someone says it’s raining, and another person says it’s dry, it’s not your job to quote them both. Your job is to look out the window and find out which is true.” Alas, if only the issues discussed in the news were this simple.

Most of the contentious issues in the news require tremendous context to understand the facts, and any single article will invariably choose a particular frame of reference and select facts to paint that viewpoint.

A long-running example is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Simply reporting that there was an attack and a certain number of people were killed is seldom sufficient to help the public understand what is going on. What precipitated the attack? Was the attack proportional to the stated reasons? What statements were released by either party in the aftermath? And, with a conflict that extends for decades, how far back in history should the journalist go to explain the reasons for an event?

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

To answer these questions, journalists provide additional context such as the scene on the ground, what events preceded the attack, and why it may have happened. This is where accusations of bias arise. But, as any Israeli or Palestinian will tell you, this issue is complex and needs multiple perspectives to get the full story. This is why many journalists often quote both sides, even if imperfectly, because they know that issues are complex and the public wants a comprehensive understanding of topics.

Embracing Bias

New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen is an astute critic of the media. He often rails against bothsidesism as “the view from nowhere” — a writing style without a clear point of view of what are the facts:

“If in doing the serious work of journalism–digging, reporting, verification, mastering a beat–you develop a view, expressing that view does not diminish your authority. It may even add to it. The View from Nowhere [a bid for trust that advertises the viewlessness of the news producer] doesn’t know from this. It also encourages journalists to develop bad habits. Like: criticism from both sides is a sign that you’re doing something right, when you could be doing everything wrong.”

Rosen advocates for journalists to be clear about their background, and frame of reference, rather than hide it. There is no attempt to occupy some mythical neutral position, and journalists are free to report on a topic as they see and know it.

Rosen’s advice is sound and practiced by many highly respected news outlets such as Reason (Libertarian viewpoint), The Intercept (Pro civil-liberties), The American Conservative (foreign policy de-escalation), and Grist (climate change urgency). However, for journalists and outlets that follow his guidance, the consequence is that as readers you must read more than one viewpoint from across the political spectrum to get the complete story. This can be time-consuming on every issue, which is why sites like The Factual try to make it easy to find these differing viewpoints.

Please check your email for instructions to ensure that the newsletter arrives in your inbox tomorrow.

Understanding the “Other Side” Makes for Better Decisions

Perhaps the most serious charge against “bothsidesism” is false equivalence — “the practice of giving equal media time and space to demonstrably invalid positions for the sake of supposed reportorial balance.”

Particularly when it comes to issues that are seemingly clear, like climate change, where 97% of scientists agree climate change is being driven by humans, isn’t presenting both sides giving undue space to the 3% of scientists that disagree?

Outspoken entrepreneur David Heinemeier Hansson puts it nicely:

“If you read The Uninhabitable Earth by Wallace-Wells or Hickel’s Less Is More in isolation (two books I’ve highly recommended!), you’ll almost certainly come away in both a state of panic and with a passion of #degrowth. They both build very persuasive narratives.

But your understanding will deepen immensely if you compliment such books with the likes of Apocalypse Never by Shellenberger. Not because you’ll be convinced that climate change isn’t a serious, urgent problem (it so very much is!), but because you’ll be better prepared for a discussion of what to do about it. Like the critical examination of, say, whether closing all the nuclear plants in Germany in favor of almost exclusively focusing investments in wind and sun was a good idea (Shellenberger makes a very convincing argument that it was not).”

David’s point illustrates how “both sides” need not be in opposition to each other. Rather, “both sides” may be more accurately described as “multiple viewpoints”. And with most issues being so complex, it makes sense to review multiple viewpoints to understand different solutions to problems.

What’s Best for the Public

Journalists may worry the public won’t come to the right conclusions if presented with contrasting viewpoints. However, this is an assumption about the reader’s critical thinking skills and, as a journalist, it’s better to assume that your reader is capable of reaching logical conclusions when given all the facts.

Famed physicist Richard Feynman once said “Religion is a culture of faith; science is a culture of doubt.” Journalism should be closer to science than religion, and hence it is perfectly reasonable to highlight criticism of a prevailing viewpoint. Most readers will likely still go with the consensus opinion but be more confident about their decision because they’ll have seen all the facts. And in a democracy, aiming for an informed majority is better than aiming for 100% blind faith.